Blue Quartz

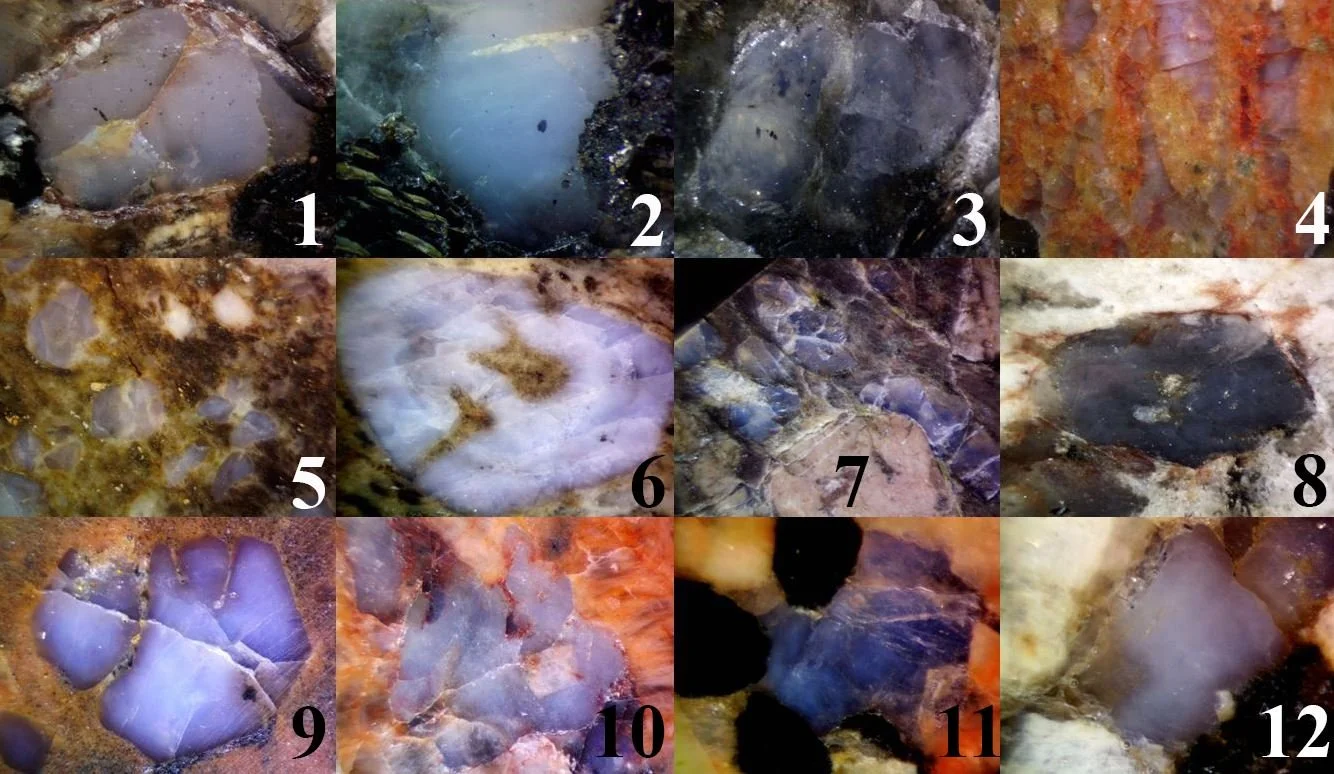

Polished sections of various blue quartz occurrences as seen under the stereographic microscope: 1-3 Albești metagranite (Romania); 4 Cosăuți granite (Moldova); 5-6 Pietrosu Bistriței porphyroid (Romania); 7 Rio dos Remédios alkali rhyolite (Bahia, Brazil); 8 Lalu granite (Romania); 9 Llano rhyolite (Texas, USA); 10 Milbank granite (South Dakota, USA); 11 Småland granite (Sweden); 12 Valea Bolovanului granite (Romania).

The journey to understand blue quartz begins with a fundamental challenge: it has no formal definition. My research starts by proposing one, designed to be as comprehensive and scientifically robust as the phenomenon itself.

From the scattered geological literature, a vague picture emerges where "blue quartz" typically refers to Proterozoic magmatic or metamorphic quartz, colored by the scattering of light from tiny mineral inclusions. However, this conventional view is unnecessarily restrictive.

Why should the Proterozoic have a monopoly on this phenomenon? We find compelling occurrences both in the older rocks of the Archean and the younger ones of the Phanerozoic. There is no objective geological reason to exclude them. A true definition must be based on the universal cause of the color, not the age of the rock.

Furthermore, if the core mechanism is truly the scattering of light—as decades of research suggest—then we must also include quartz colored by scattering from structural features like lattice defects or microfractures. The origin of the scatterer is secondary to the physical process that creates the visual effect.

Therefore, I propose a more inclusive and precise definition for my research:

Blue quartz encompasses all but the cryptocrystalline and amorphous forms of SiO₂ whose color results from the scattering of light, irrespective of the geological age, geological setting, or the specific nature of the scattering centers.

This definition intentionally excludes quartz that appears blue for other reasons, such as the presence of intrinsically blue mineral inclusions like dumortierite, tourmaline, or riebeckite. While beautiful, these are simply colored by the minerals they contain; they are a reflection of local geological conditions. My focus is on the fundamental scattering process itself, which cuts across different ages and geological environments, presenting a coherent, global puzzle to be solved.

The Physics of the Blue: Unraveling the Scattering Mechanism

A beautiful example of atmospheric Rayleigh scattering during sunrise/sunset (Photo: https://beautifulnow.is/discover/nature-science/science-explains-why-red-skies-happen-at-sunrise-and-sunset-and-why-they-are-all-more-beautiful-in-autumn).

Simply put, think of the quartz crystal as a crowded street and light as a beam of sunshine. When the light enters the crystal, it bumps into incredibly tiny particles trapped inside—so small that they interact more with the blue light than with the red. These particles effectively "kick" the blue light out to the sides, making the crystal itself appear blue when you look at it. The exact shade and intensity depend on the size and nature of these hidden particles, which is what my research aims to discover.

The captivating blue color of my research subjects is not a result of pigment, but of a phenomenon known as light scattering. At its core, scattering is the deviation of light from a straight path when it encounters an obstacle. This is closely related to both reflection and diffraction. Imagine a parallel beam of light hitting a small, reflective surface. If that surface is only slightly larger than the light's wavelength, the reflected light will spread out a little at the edges due to diffraction. Now, imagine shrinking that reflector until it is much smaller than the wavelength of light. The scattering becomes so extreme that the light is sent out in all directions, forming a spherical wave. At this point, the light is said to be scattered, rather than reflected, because the object is too small to obey the classical law of reflection. Therefore, scattering is essentially a special case of diffraction.

The micro/nano interaction

In general, when light, which is an oscillating electromagnetic wave, passes through a medium, its electric field perturbs the electrons of the atoms it encounters. These disturbed electrons begin to oscillate in response, becoming tiny, vibrating dipoles that re-emit light as secondary waves. The collective interference of these myriad secondary waves with the original light beam is what causes the scattering we observe.

The first quantitative study of scattering by such small particles was performed in 1871 by Lord Rayleigh. For particles with linear dimensions considerably smaller than the wavelength, the intensity of the scattered light is proportional to the inverse fourth power of the wavelength (1/λ⁴). This means violet light is scattered about ten times more effectively than red light. If white light is scattered by sufficiently fine particles, like those in tobacco smoke, the scattered light will always have a bluish tint. This is the same process that makes the sky blue. However, its classical formulation assumes spherical particles, and its direct application to the likely needle-shaped mineral inclusions in quartz remains an open question.

If the particle size is increased until they are no longer small compared to the wavelength, the scattered light becomes white, due to ordinary diffuse reflection. The distinctive blue color from very small particles and its dependence on size was first studied experimentally by Tyndall. Tyndall Scattering applies to this slightly larger particle range, typically 40-900 nm, and often produces a more intense blue, as seen in the blue haze of diesel exhaust.

For both mechanisms, the same principle creates the color: the shorter blue wavelengths are scattered away from the main beam more efficiently than the longer red wavelengths. Consequently, when you look through a piece of blue quartz, you might see a reddish tinge where the blue has been removed, while the scattered light you see from the side is dominantly blue.

The critical role of the refractive index

A key factor in this process is the refractive index. The efficiency of scattering is not just about particle size; it is also governed by the contrast in refractive index between the inclusion and the surrounding quartz. The mathematical investigation of scattering gives a general law for the intensity of scattered light, applicable to any particle with a refractive index different from its surrounding medium. Materials with a higher electron density and polarizability have a higher refractive index, meaning their electrons oscillate more readily when hit by light, thereby scattering it more effectively. This fundamental connection, described by relationships like the Clausius-Mossotti equation, means that identifying the scattering centers is not just about finding tiny particles, but finding the *right kind* of tiny particles with a significant refractive index mismatch against the quartz host.

An open scientific question

While these principles provide a theoretical framework, their precise application to blue quartz is a central part of my research. Are we observing true Rayleigh scattering, Tyndall scattering, or a complex combination? What is the exact size, shape, and mineral identity of the inclusions that create the necessary refractive index contrast? Answering these questions is essential to moving from a general "scattering" explanation to a definitive, predictive model for the formation of blue quartz.

The Core Controversy: Does Size Matter?

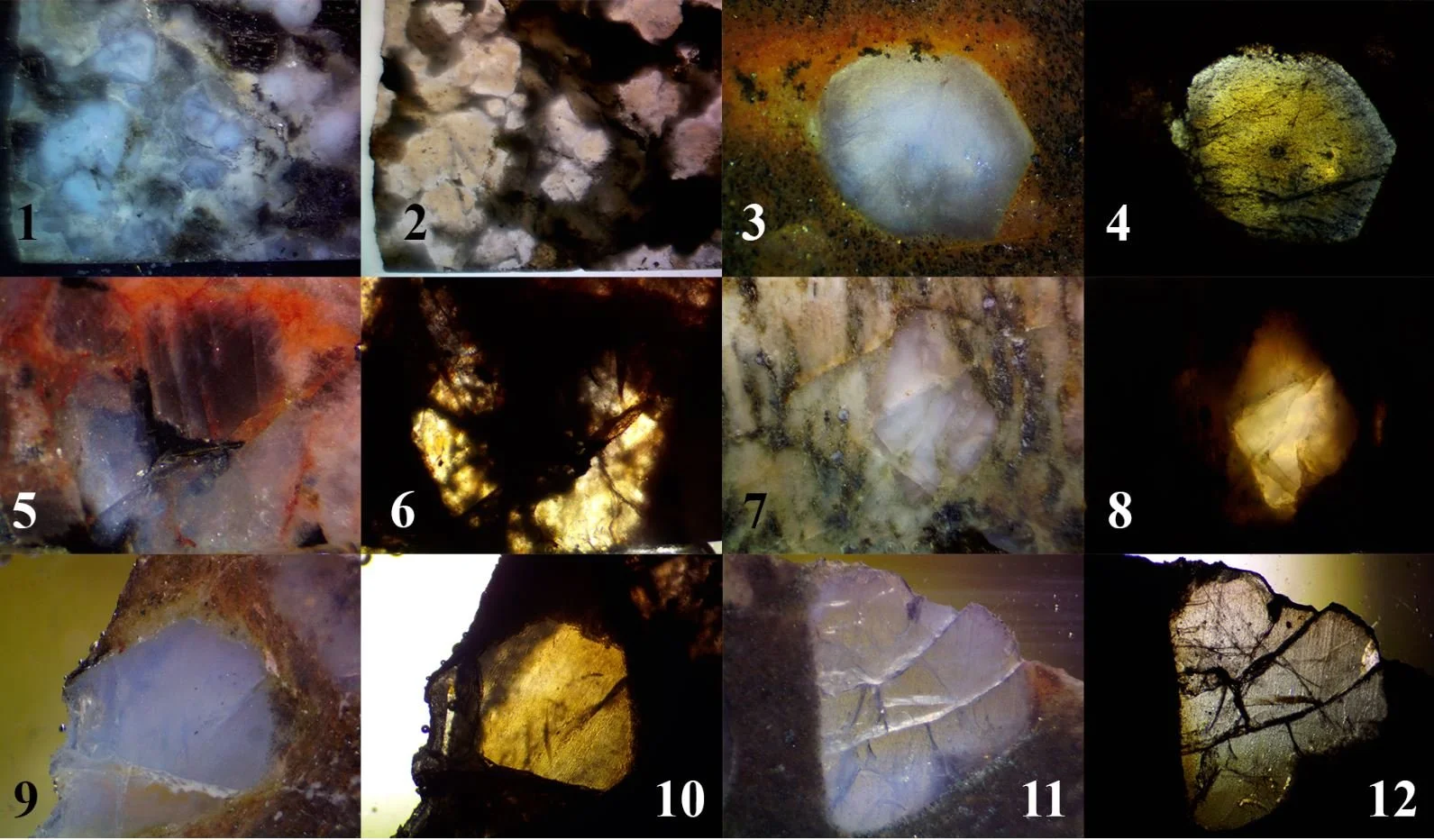

Color differences in reflected/transmitted light: 1-2 Albești granite (Romania); 3-4 Llano rhyolite (Texas, USA); 5-6 Milbank granite (South Dakota, USA); 7-8 Pietrosu Bistritei porphyroid (Romania); 9-10 and 11-12 Rio dos Remédios alkali rhyolite (Bahia, Brazil).

The central mystery of blue quartz lies in the identity and size of the "scattering centers"—the features responsible for its color. A century of scientific literature reveals a startling lack of consensus, with reported inclusion sizes varying wildly from less than 27 nanometers to over 800 nanometers. This discrepancy is not minor, and strikes at the very heart of our understanding of the phenomenon.

A century of contradictory evidence

The historical record is a tapestry of conflicting measurements. Early researchers like Iddings (1904) and Moore (1911) proposed sizes up to 800 nm or "less than half the wavelength of light." Later studies narrowed the range, with some, like Zolensky et al. (1988), pinpointing 60 nm inclusions at an incredibly high density, while others, such as Seifert et al. (2011), contested those very findings for the same location, reporting a density a hundred times lower. Some inclusions described, like the 0.1x1x20 μm rods in Llano quartz, are large enough to cause chatoyance ("cat's eye effect") but are considered by many to be too large to efficiently scatter blue light. The simple fact that many of these inclusions are visible under a standard petrographic microscope suggests they are at least 300 nm in size, placing them at the upper limit—or beyond—of what traditional scattering theory often allows.

Two competing hypotheses

This chaos in the data points toward two compelling possibilities:

The "Wrong Inclusions" Hypothesis: If the critical size for efficient blue-light scattering is indeed below ~55 nm, then most of the inclusions reported in the literature are simply too large to be the primary cause. This would force a paradigm shift, suggesting we must look for other, previously overlooked scattering features, such as nanoscale lattice defects or microfractures, which are invisible to conventional microscopy.

The "Size-Density Interplay" Hypothesis: Alternatively, if inclusions in the 300-500 nm range can effectively scatter light, then the wide range of reported colors could be explained by a delicate balance. The intensity and hue of the blue would be a function of both the size of the inclusions and their spatial density within the quartz. A lower density of very small inclusions might produce a pale blue, while a higher density of larger inclusions could create a deeper, more saturated color.

The very breadth of the reported dimensions could also indicate a more fundamental issue: a long-standing reflex to label the smallest identifiable inclusions as the cause, potentially missing the true, sub-microscopic actors entirely.

The broader context: scattering in nature

The phenomenon preferantial scattering of the blue part of the spectrum is not unique to quartz. Nature employs the same physics in other materials, providing valuable comparative case studies:

Blue Zhamanshinite: Contains ~100 nm spherical silicate glass inclusions (Zolensky & Koeberl, 1991).

Blue Fulgurite: Features ~100 nm silica-rich nanospheres (Feng et al., 2019).

Blue Zircon: Colored by actinide-rich inclusions below 100 nm (Sun et al., 2020).

Río Celeste: Its famous turquoise waters are caused by the scattering of light from 566 nm mica particles in suspension (Castellón et al., 2013).

This comparative view is illuminating. It shows that while the ~100 nm size range is common, effective scattering centers can exist at larger scales, as in the Río Celeste. This reinforces the idea that a single, rigid size limit may be insufficient, and that the refractive index contrast and particle geometry are equally critical factors.

My research is designed to cut through this historical uncertainty by applying modern nano-analytical techniques to systematically measure the size, density, and composition of inclusions and correlate them directly with optical properties, finally resolving this century-old debate.

The Suspects and Their Origins: Unmasking the Scattering Centers

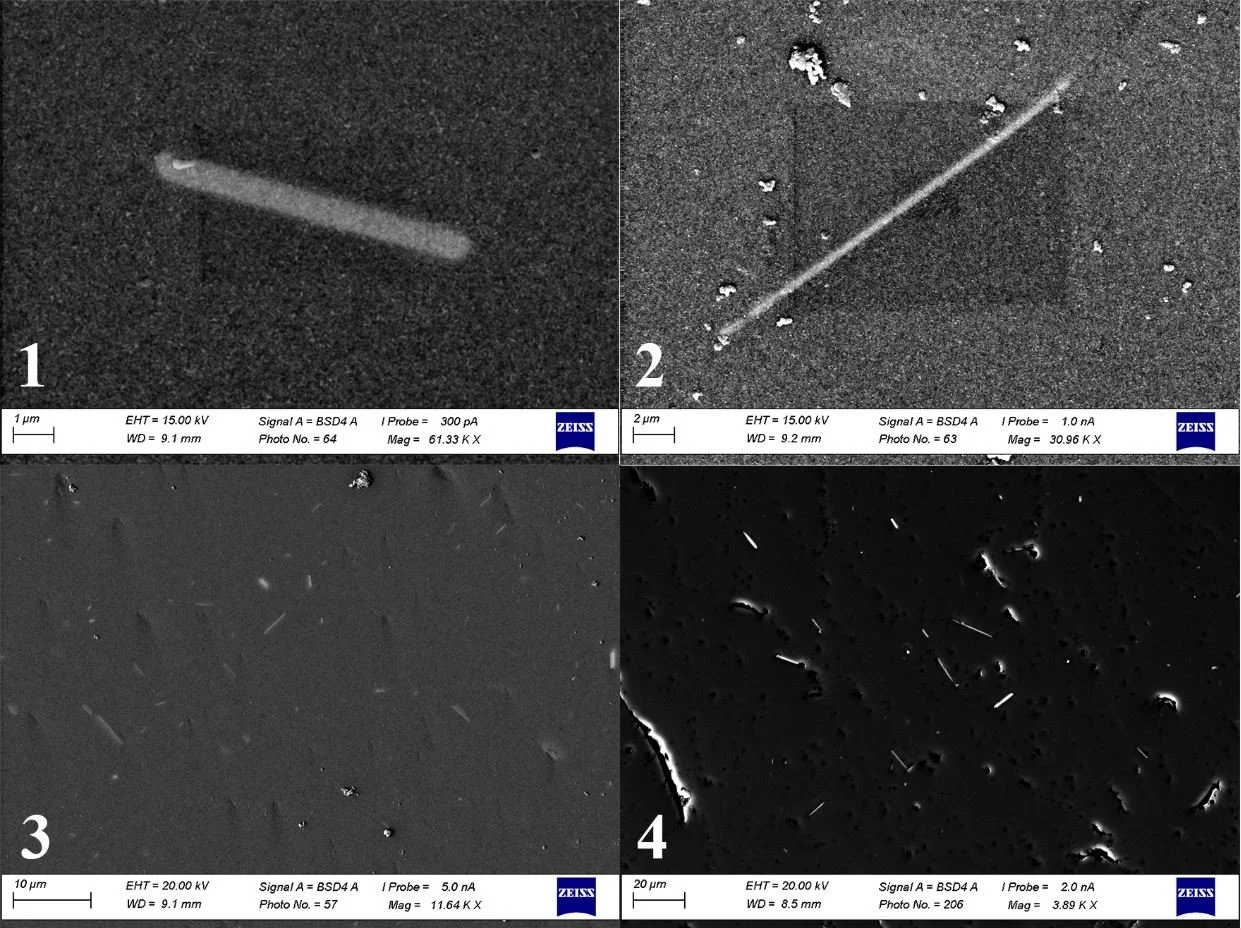

Submicron rutile inclusions in: 1 Albești granite (Romania), 8/0.63 μm; 2 Llano rhyolite (Texas, USA) 21/0.37 μm; 3 Milbank granite (South Dakota, USA) 3.78/0.07 μm on average; 4 Pietrosu Bistriței porphyroid (Romania) 8.5/0.33 μm on average.

Blue of quartz is a captivating, more or less understood, physical phenomenon, but its precise cause is a geological puzzle. Identifying the "scattering centers"—the nanoscale features responsible for the color—and understanding their origin is the central challenge of this research. The mineral most frequently cited is rutile (TiO₂), and for compelling physical reasons. With one of the highest refractive indices of any natural mineral (~2.6–2.9), rutile scatters light with an intensity that scales with (n²-1)², making it ~10–100 times more effective than common low-index minerals like muscovite. This is why even small rutile particles in suspension cause strong Tyndall scattering. Furthermore, the presence of Ti in quartz is easely explained, and rutile exsolution is well known.

However, effective scattering requires a sufficient refractive index contrast (Δn) between the inclusion and the quartz host (Δn ≥ ~0.1). Rutile and ilmenite provide this easily, but they are not the only candidates. A suite of other minerals has been proposed (arguably based on observation alone), including biotite, tourmaline, zircon, apatite, graphite, magnetite, hematite, plagioclase, titanite, carbonaceous material, mica, zoisite, and even fluid inclusions.

The rutile enigma: contradictory evidence

The evidence for rutile is extensive but fraught with contradiction. This is perfectly illustrated by studies of the Rumburk granite in Germany. Seifert et al. (2009) pointed to <500 nm thick rutile needles as the cause of the coloration. Intriguingly, a follow-up study by Seifert et al. (2010) on different samples from the same occurrence found no rutile in the matrix or quartz, leading them to conclude that the color is not exclusively due to rutile. Yet another investigation by Seifert et al. (2011) once again reported rutile in the blue quartz of the Rumburk granite.

This inconsistency is not isolated. For the Hillgrove Suite granite, Hensel (1982) cited rutile as the likely cause, while Landenberger (1996), studying the same occurrence, found no evidence of it. Similarly, Bartholomäus & Solcher (2002) and Landenberger (1996) note other blue quartz occurrences where no light-scattering inclusions have been identified at all. A telling case comes from the Tim-Yastrebovskaya structure in Russia, where Kholina et al. (2016) reported that the rutile content in two neighboring samples varied by a factor of 10 (from 0.5% to 5%), suggesting that if the color is consistent, rutile cannot be the sole agent.

Genetic mechanisms: how do scattering centers form?

The presence of these nanoscale features is attributed to several sophisticated petrogenetic processes:

Exsolution is the most cited mechanism by far, as rutile is also the most cited scattering center.

Strain is frequently identified as a facilitator for the precipitation of scattering inclusions.

Syngenetic formation with the host quartz or the addition of pre-existing minerals from the melt during grain growth.

Redistribution of lattice-bound impurities. Müller et al. (2002) proposed that multiple deformations cause the accumulation of Al and K in <500 nm muscovite-like inclusions. A similar mechanism involving strain and lattice-bound Ti was suggested by Poller (1997).

Recrystallization Purification. Crucially, the experimental work of Thomas & Nachlas (2020) demonstrated that dry grain boundary migration recrystallization of Ti-rich quartz (349-392 ppm) can directly produce randomly oriented rutile needles (>100 μm long and 100-750 nm thick) in the wake of the migrating boundary. This provides a robust experimental model for one formation pathway. Furthermore, Müller et al. (2007) pointed to the concentration of impurities along grain boundaries and in microscopic inclusions as a direct result of quartz lattice purification during recrystallization.

Decoding color zonation

A critical clue in this mystery is the common presence of color zoning, where blue color is confined to discrete, often rounded bands within quartz grains. According to Seifert et al. (2011), this zonation is incompatible with deformational processes and indicates the scattering centers are of primary magmatic origin.

Detailed studies of zoned grains reveal a direct correlation between color and inclusion density. In the Llano blue quartz, the color difference between the blue core and the darker rim is attributed to two factors: 1) the core contains a greater proportion of nanometric ilmenite inclusions capable of scattering light (Zolensky et al., 1988), and 2) the spatial density of inclusions is significantly higher in the core (1.1-1.7 inclusions/μm³) than in the rim (0.4-0.6 inclusions/μm³) (Seifert et al., 2011). For comparison, blue zircon from Mt. Vesuvius has a reported density of >5 inclusions/μm³ (Sun et al., 2020).

This spatial density gradient is chemically grounded. Seifert et al. (2011) measured the Ti content and applied Ti-in-quartz thermometry to zoned grains, finding that the blue cores contain roughly twice the Titanium of the rims and crystallized at temperatures 100-110 °C higher. This direct correlation between Ti concentration, crystallization temperature, inclusion density, and color intensity—also suggested by early researchers like Moore (1911) and Herz & Force (1987)—provides a powerful framework for understanding how the geological history of a quartz grain is encoded in its color.

A Global Puzzle: Mapping the Occurrences of Blue Quartz

The global distribution of magmatic and metamorphic blue quartz occurrences.

Cataloging the global occurrences of blue quartz is a foundational yet formidable challenge. The scientific literature often proves to be an inconsistent witness; some studies fail to report the color at all, while others describe it inadequately. The same rock unit can be described differently across various papers. For instance, the Sunflower granite in the USA has been described as both blue and milky blue (Spencer et al., 2004), while other occurences were identified as sky blue, greyish blue, bluish grey, dove blue, or Oxford blue. Furthermore, blue quartz can be misclassified as grey, and grey quartz can be described as bluish or blue-grey.

This selective reporting is widespread. Wade (2011) reports blue quartz in the Nooldoonooldoona and Mindamereeka trondhjemites of Australia, yet Jaireth et al. (2015) mention it only at Mindamereeka, not Nooldoonooldoona. Similarly, Cornell et al. (2023) describe blue quartz in the Zoutpekel porphyroid of South Africa, while Grobler et al. (1977) describe the same quartz as merely opalescent. In Venezuela and Colombia, Pérez et al. (2013) note the blue color of quartz in the Paraguaza granite, whereas Gaudette et al. (1978), in a paper dedicated to the same granite, make no comment on its color. An additional complication arises in ore deposit contexts, where described "blue quartz" may refer to silicification products rather than the primary, rock-forming variety that is the focus of this study.

A first-of-its-kind catalogue

Despite these inherent uncertainties in a literature that is often only tangential to the subject, I have compiled a catalogue of approximately 800 reported occurrences, documented with varying degrees of accuracy. Even assuming a 25% error rate in reporting and interpretation, a robust dataset of around 600 occurrences remains to provide an overview of the global distribution pattern. While earlier researchers like Wise (1981) and Bartholomäus & Solcher (2002) noted the global scale of blue quartz, the true magnitude of its distribution has likely been underestimated.

Emerging patterns: orogens, greenstone belts, and anorthosites

The compiled data reveals that blue quartz is not randomly distributed. The occurrences cluster in terms of both geography and age, outlining major magmatic and metamorphic episodes associated with Earth's major orogenic events. These include the Trans-Hudson, Grenville, Pan-African, Appalachian, and Hercynian orogenies, followed by greenstone belts (e.g., Flin Flon, Kolar, Abitibi) and local episodes of intra-plate granitic magmatism.

At a regional scale, distinct clusters of occurrences are often tightly associated with single anorthosite intrusions, particularly in Canada (the Lac-Saint-Jean, Rivière-Pentecôte, Nain, and Doré Lake plutons), but also in Brazil (Cana Brava), South Africa (Bushveld), and Angola (Kunene). At this stage of data collection and understanding, these associations are working hypotheses. They strongly suggest, however, that a significant proportion of blue quartz occurrences are linked by regional and continental-scale geological events, representing not local accidents but the result of geochemical and physical particularities manifest on the scale of great orogens from the Archean to the present.

A key absence and its implications

A finding of particular interest is the apparent absence of reported blue quartz occurrences in Avalonian terranes in both Europe and North America. This absence is most simply and clearly illustrated in Newfoundland, where a clear demarcation exists between the peri-Laurentian, Ganderia, and Avalonia domains—with the latter being devoid of blue quartz.

In contrast, the blue quartz-bearing terranes of peri-Gondwanan Europe are of Cadomian provenance, with a characteristic host-rock age between approximately 490-460 Ma. This distinction has potential tectonic significance. For example, Munteanu & Tatu (2003) assigned an East Avalonian affinity (and thus Caledonian accretion) to the Pietrosu Bistriței porphyroid. However, based on its characteristic blue quartz content, it is more similar to European Cadomian occurrences than to Avalonian terranes. While not conclusive, this finding underscores the need to re-evaluate the provenance of the Rebra-Tulgheș terrane.

A chronological span of 3 billion years

The age of blue quartz is far less restricted than previously suggested. While Zolensky et al. (1988) and Seifert et al. (2011) arbitrarily restricted it to the Precambrian and pre-Hercynian, respectively, the compiled data reveals a chronological span of over 3 billion years. This range extends from the ~3000 Ma Aghaming tonalite in Canada (Percival et al., 2000), through the transcontinental Grenville-age occurrences (~1300-1100 Ma), the ~480 Ma average age of peri-Gondwanan European occurrences, to the ~57 Ma Rhyolite Creek tonalite in Canada (Israel et al., 2011), and even the remarkably young 0.9-0.23 Ma Los Pueblitos rhyolite in Mexico (Rossotti et al., 2002).

A final layer of complexity is added by metamorphism. If a metamorphic episode can generate the blue color, it is difficult to determine from bibliographic resources alone whether the rock's age is the same as the color's age, or if the color is younger, having appeared during one of the multiple metamorphic events often recorded by the host rock. This uncertainty complicates the interpretation of the global occurrence pattern but also opens a fascinating avenue for future research into the timing of this enigmatic coloration.

References

Bartholomäus, W.A., Solcher, J. 2002. Wenig bekannte Eigenschaften von Blauquarz (The less known properties of blue quartz). Geschiebekunde Aktuel, 118(3): 99-106.

Castellón, E., Martínez, M., Madrigal-Carballo, S., Arias, ML., Vargas, WE., Chavarría, M. 2013. Scattering of Light by Colloidal Aluminosilicate Particles Produces the Unusual Sky-Blue Color of Río Celeste (Tenorio Volcano Complex, Costa Rica). PLoS ONE 8(9): e75165. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075165.

Cornell, D., Meintjes, G., van der Westhuizen, W., Frei, D. 2023. Are the Ventersdorp Supergroup and Marydale Group coeval? Geocongress 2023 Abstracts, Geocongress 2023, The next 125 years of Earth Sciences, p. 39.

Feng, T., Lang, C. & Pasek, M.A. 2019. The origin of blue coloration in a fulgurite from Marquette, Michigan. Lithos, 342-343: 288-294.

Gaudette, H.E., Mendoza, V., Hurley, P.M., Fairbairn, H.W. 1978. Geology and age of the Parguaza rapakivi granite, Venezuela. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 89:1335-1340.

Grobler, N.J., Botha, B.J.V., Smit, C.A. 1977. The tectonic setting of the Koras Group. Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa, 80: 167-175.

Hensel, H. D. 1982. The mineralogy, petrology and geochronology of granitoids and associated intrusives from the southern portion of the New England Batholith. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of New England, Armidale, N.S.W.

Herz, N., Force, E.R. 1987. Geology and mineral deposits of the Roseland District of Central Virginia. Professional Paper. U. S. Geological Survey. 1371: 56 pp.

Iddings, J.P. 1904. Quartz-feldspar-porphyry (graniphyro liparose-alaskose) from Llano, Texas. The Journal of Geology, 12(3): 225-231.

Israel, S., Murphy, D., Bennett, V., Mortensen, J., Crowley, J. 2011. New insights into the geology and mineral potential of the Coast Belt in southwestern Yukon. In: MacFarlane, K.E., Weston, L.H., Relf, C (editors). Yukon Exploration and Geology 2010, Yukon Geological Survey, p. 101-123.

Jaireth, S., Roach, I.C., Bastrakov, E., Liu, S. 2015. Basin-related uranium mineral systems in Australia: A review of critical features. Ore Geology Reviews 76: 360-394.

Kholina, N.V., Savko, K.A., Kholin, V.M. 2016. Visokiye temperatury kristallizatsii neoarkheyskikh Kurkogo Bloka Voronezhskogo Kristallichesskogo Massiva: rezultaty mineralnoy termometrii (High crystallization temperatures of the Neoarchean rhyolites of the Kursk Block of the Voronezh Crystalline Massif: results of mineral thermometry). Bulletin of the Voronezh State University. Series: Geology, 3: 53-60.

Landenberger, B. 1996. Petrogenesis and tectono-magmatic evolution of S-type and A-type granites in the New England Batholith. A Thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 310p.

Moore, E.S. 1911. The Sturgeon Lake Gold Field. In: Twentieth Annual Report of the Bureau of Mines, vol. XX, part. I, Ontario, pp. 133-157.

Müller, A., Lennox, P., Trzebski, R. 2002. Cathodoluminescence and micro-structural evidence for crystallization and deformation processes of granites in the Eastern Lachland Fold Belt (SE Australia). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 143: 510-524.

Müller, A., Ihlen, P.M., Wanvik, J.E. 2007. High-purity quartz mineralisation in kyanite quartzites, Norway. Mineralium Deposita, 42: 523-535.

Munteanu, M., Tatu, M. 2003. The East-Carpathian Crystalline-Mesozoic Zone (Romania): Paleozoic amalgamation of Gondwana- and East European craton-derived terranes. Gondwana Research, 6(2): 185-196.

Percival, J.A., Bailes, A.H., Corkery, M.T., Dubé, B., Harris, J.R., McNicoll, V., Panagapko, D., Parker, J.R., Rogers, N., Sanborn-Barrie, M., Skulski, T., Stone, D., Scott, G.M., Tomlison, K.Y., Whalen, J.B., Young, M.D. 2000. Western Superior NATMAP: an integrated view of Archean crustal evolution. Report of Activities 2000, Manitoba Industry, Trade and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 108-116.

Pérez, A.B., Frantz, J.C., Charão-Marques, J., Cramer, T., Franco-Victoria, J.A., Mulocher, E., Perea-Amaya, Z. 2013. Petrografía, geoquímica y geocronología del granite de Parguaza en Colombia. Boletín de Geologia, 35(2): 83-104.

Poller, U. 1997. U-Pb single zircon study of gabbroic and granitic rocks of Val Barlas-ch (Silvretta nappe, Switzerland). Schweiz. Mineral. Petrogr. Mitt. 77: 351-359.

Rossotti, A., Ferrari, L., López-Martínez, M., Rosas-Elguera, J. 2002. Geology of the boundary between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt in the Guadalajara region, western Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 19(1): 1-15.

Seifert, W., Rhede, D., H.-J. Förster, Thomas, R. 2009. Accessory minerals as fingerprints for the thermal history and geochronology of the Caledonian Rumburk granite. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Abhandlungen, 186(2): 215-233.

Seifert, W., Thomas, R., Rhede, D., Förster, H.-J. 2010. Origin of coexisting wüstite, Mg-Fe and REE phosphate minerals in graphite-bearing fluorapatite from the Rumburk granite. European Journal of Mineralogy, 22: 495-507.

Seifert, W., Rhede, D., Thomas, R., Forster, H.-J., Lucaseen, F., Dulski, P., Wirth, R. 2011. Distinctive properties of rock-forming blue quartz: inferences from a multi-analytical study of submicron mineral inclusions. Mineralogical Magazine, 75(4): 2519-2534.

Spencer, J.E., Leighty, R.S., Conway, C.M., Ferguson, C.A., Richard, S.M. 2004. Compilation geologic map of the Reno Pass area, central Mazatzal Mountains, Maricopa and Gila Counties, Arizona. Arizona Geological Survey, Open File Report 04-03, 15p.

Sun, Y., Schmitt, A.K., Häger, T., Schneider, M., Pappalardo, L., Russo, M. 2020. Natural blue zircon from Vesuvius. Mineralogy and Petrology, 115: 21-36.

Thomas, J.B., Nachlas, W.O. 2020. Discontinuous precipitation of rutilated quartz: grain-boundary migration induced by changes to the equilibrium solubility of Ti in quartz. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 175:38, 16 p.

Wade, C.E. 2011. Definition of the Mesoproterozoic Ninnerie Supersuite, Curnamona Province, South Australia. Mathematics in Engineering, Science and Aerospace Journal, 62: 25-42.

Wise, M. A. 1981. Blue quartz in Virginia. Virginia Minerals, 27(2): 9-12.

Zolensky, M.E., Sylvester, P.J., Paces, J.B. 1988. Origin and significance of blue coloration in quartz from Llano rhyolite (llanite), north-central Llano County, Texas. American Mineralogist, 73: 313-323.

Zolensky, M.E.,Koeberl, C. 1991. Why are blue zhamanshinites blue? Liquid immiscibility in an impact melt. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 55: 1483-1486.